d modern composite engineering by decades.

A search for lighter, cheaper cars

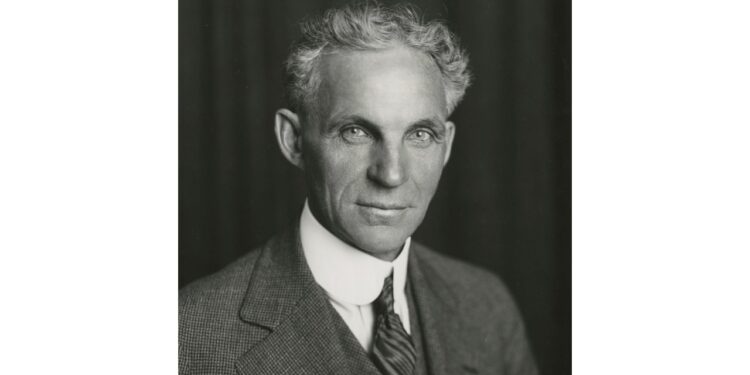

By the late 1930s, Henry Ford had become increasingly concerned about material costs, vehicle weight, and dependence on steel. The Great Depression and looming geopolitical tensions sharpened his belief that the future of manufacturing required flexibility, domestic raw materials, and innovation beyond traditional metals. Ford believed that lighter cars would be more fuel-efficient, cheaper to produce, and safer, while also insulating American industry from volatile steel supply chains.

The patented plastic concept

Ford’s answer was a structural plastic body mounted on a tubular steel frame. Working with chemists and engineers at Ford Motor Company, he supported the development of a composite material made from phenolic resin reinforced with plant fibres such as soy, wheat, hemp, flax, and ramie. Several patents filed under Ford’s direction covered moulded plastic panels, bonding techniques, and modular body construction methods. These patents outlined not decorative parts, but load-bearing exterior panels designed for full vehicle use.

The 1941 ‘plastic car’ demonstration

In 1941, Ford publicly unveiled an experimental vehicle often referred to as the “soybean car”. The plastic-bodied automobile weighed roughly 30 percent less than comparable steel cars and was claimed to be more resistant to dents and corrosion. In a now-famous demonstration, Ford struck the rear panel with an axe to show its resilience. While partly theatrical, the demonstration highlighted the material’s structural durability and impact resistance—key concerns for automotive safety even at that time.

Industrial and economic rationale

Ford’s interest in plastic automobiles was not merely technical. It formed part of his broader vision of vertical integration between agriculture and industry. By sourcing raw materials from American farms, Ford sought to stabilise rural incomes while reducing reliance on imported or strategically sensitive materials. The plastic car aligned with his long-standing philosophy that industrial progress should support national self-sufficiency and economic resilience.

Why the idea stalled

Despite successful prototypes and patented processes, the project never reached mass production. The outbreak of the Second World War redirected industrial capacity toward military output, while steel shortages paradoxically increased demand for conventional metal manufacturing. After the war, oil-derived plastics became dominant, undercutting Ford’s plant-based material strategy. Henry Ford’s death in 1947 removed the project’s strongest internal champion, and corporate priorities shifted toward scale and standardisation.

A legacy ahead of its time

In retrospect, Ford’s plastic automobile concept appears strikingly modern. Today’s vehicles rely extensively on composites, polymers, and lightweight materials to meet efficiency and emissions targets. Ford’s patented ideas foreshadowed contemporary automotive design principles by more than half a century. While his plastic car never entered production, it remains a powerful reminder that innovation often precedes its commercial moment.

Newshub Editorial in North America – 13 January 2026

Recent Comments