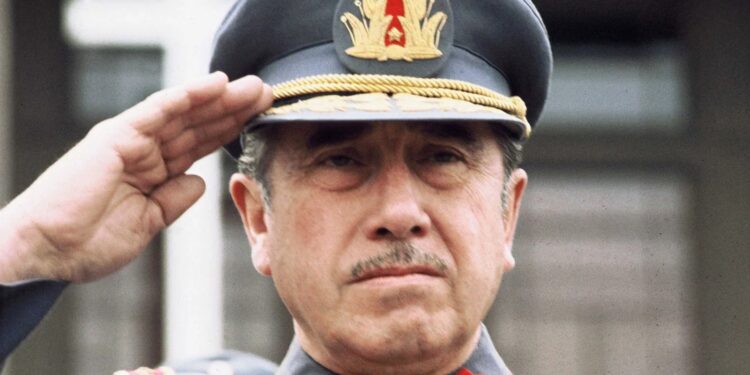

General Augusto Pinochet remains one of the most polarising figures in modern Latin American history, associated both with the overthrow of Salvador Allende’s socialist government in 1973 and with a 17-year military regime marked by economic overhaul and widespread human-rights abuses. His rule continues to shape Chile’s political landscape as the country confronts unresolved questions about truth, justice and democratic resilience.

A coup that reshaped Chile

Pinochet seized power on 11 September 1973 in a violent military coup that ended Allende’s presidency and abruptly halted Chile’s democratic order. Backed by the armed forces and initially supported by parts of the business community and foreign actors wary of Allende’s socialist project, Pinochet presented his takeover as a necessary intervention to stabilise the country. The coup resulted in immediate repression, with political opponents detained, exiled or killed as the regime consolidated authority.

Authoritarian rule and human-rights abuses

Pinochet dissolved Congress, banned political parties and placed strict controls on media and civil society. According to later truth-commission findings, more than 3,000 people were killed or disappeared and tens of thousands were tortured. Detention centres, including the notorious Villa Grimaldi, became symbols of state-sanctioned violence. Families of victims still campaign for accountability, citing slow judicial progress and gaps in public acknowledgement of past abuses.

Economic transformation and the ‘Chilean model’

Alongside its authoritarian apparatus, the regime implemented radical market-driven reforms designed by a group of economists often referred to as the “Chicago Boys.” Key industries were privatised, trade barriers reduced and state spending restructured. These policies contributed to long-term growth and a modernised economy, but they also entrenched inequality and weakened social protections. The model remains central to contemporary debates over Chile’s economic identity and the limits of neoliberalism.

A contested transition to democracy

Pinochet’s rule formally ended after he lost a 1988 national plebiscite, leading to a negotiated transition that preserved parts of the old order. He remained army commander until 1998 and held a lifetime Senate seat, underscoring his enduring institutional influence. His 1998 arrest in London on a Spanish warrant marked a turning point in global human-rights jurisprudence, though he ultimately returned to Chile without trial. Subsequent domestic cases eroded his impunity, but he died in 2006 without a definitive judicial reckoning.

An enduring and divisive legacy

Public opinion on Pinochet remains sharply split. Some credit him with rescuing Chile from political and economic turmoil; others underscore the systematic repression and institutional trauma his government inflicted. Recent constitutional debates, mass protests and generational shifts have revived questions about memory, accountability and the kind of nation Chile seeks to build. The unresolved tension between economic modernisation and human-rights accountability ensures Pinochet’s legacy will continue to shape national discourse.

Newshub Editorial in South America – 10 December 2025

Recent Comments