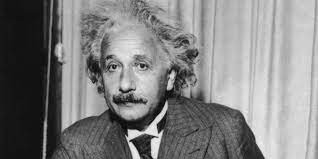

He changed the way humanity understands space, time and light — yet Albert Einstein’s greatest struggle was not with mathematics, but with the moral weight of his discoveries. Behind the iconic hair and playful smile stood a refugee, pacifist, and reluctant prophet of the atomic age, wrestling with conscience in a century of chaos.

In the pantheon of twentieth-century figures, few names carry such universal recognition as Albert Einstein. Yet his legacy is more complex than the shorthand of genius or the shorthand of E = mc². His life was defined not only by scientific brilliance but by displacement, dissent, and an unwavering commitment to moral independence.

From quiet beginnings to the voice of a century

Born in Ulm, Germany, in 1879, Einstein’s childhood gave few clues to the revolutionary thinker he would become. He disliked rigid schooling, preferring solitary daydreaming to reciting lessons. What captivated him most was the invisible magnetic fields, beams of light, and the abstract fabric of reality. By his mid-teens, he had already rejected both authoritarian discipline and religious orthodoxy, forming the habit of questioning everything that would mark his life and work.

After graduating from the Swiss Federal Polytechnic in Zurich, Einstein struggled to find academic employment and instead joined the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. The modest bureaucratic job proved serendipitous. In 1905, during what became known as his Annus Mirabilis — his miraculous year — he published four papers that rewrote physics. Among them was his special theory of relativity, showing that time and space are not absolute but interwoven, and that mass and energy are equivalent. The world’s understanding of the universe shifted in a single year.

But even at this early stage, Einstein saw science as inseparable from the human spirit. “The most incomprehensible thing about the universe,” he later wrote, “is that it is comprehensible.” For him, the search for knowledge was not only intellectual but ethical — a way of participating in the order and mystery of creation.

Exile from the homeland of reason

As Europe descended into authoritarianism, Einstein’s idealism met its greatest test. By the early 1930s, the rise of Adolf Hitler made life in Germany intolerable for Jews and dissenters. Einstein, already an outspoken critic of nationalism and militarism, found himself vilified by the Nazi press as an “enemy of the German people.”

In 1933, while travelling to lecture in the United States, he learned that his property had been seized and that a bounty had been placed on his head. He never returned. “I shall stay in this country,” he declared, “because I have the privilege to live where freedom of speech is guaranteed.”

Einstein settled at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study, where he would remain for the rest of his life. Yet exile left deep scars. He missed the cadence of his native tongue, the landscapes of Switzerland and Germany, the intellectual cafés of Europe. But he also recognised exile as a moral condition — a liberation from belonging to any state. “The state,” he wrote, “is made for man, not man for the state.”

He renounced his German citizenship and became a symbol of cosmopolitan humanism. Letters from refugees poured into his home; he answered many personally, often using his own funds to help them escape. For Einstein, intellectual freedom was inseparable from moral responsibility.

The reluctant father of the bomb

Ironically, it was Einstein’s own equation — E = mc² — that underpinned the most devastating weapon in history. As Hitler’s armies advanced, physicists feared that Germany might develop an atomic bomb. In 1939, fellow scientists Leo Szilard and Edward Teller urged Einstein to sign a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning of the danger and recommending that the United States accelerate its research into nuclear fission. Einstein agreed, though reluctantly. “I made one great mistake in my life,” he later said, “when I signed that letter to President Roosevelt recommending that atom bombs be made.”

The letter led to the Manhattan Project, and ultimately to Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Einstein took no part in the project itself, and his theoretical work was only indirectly related to its engineering, but he was haunted by the moral consequence. He spent his later years campaigning against nuclear proliferation and urging world government as the only safeguard against self-annihilation. “The splitting of the atom has changed everything,” he lamented, “except our way of thinking.”

His position was not simplistic pacifism; it was an evolving moral calculus. During the Second World War, he admitted that defeating Hitler might justify violence as the lesser evil. But he refused to let expedience replace conscience. In speeches and essays, he argued that science must serve humanity, not power. “Our task,” he wrote, “must be to free ourselves by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty.”

Faith without dogma

Though often labelled an atheist, Einstein’s view of religion was subtler. He rejected organised dogma but embraced what he called “a cosmic religious feeling” — an awe before the rational harmony of the universe. He admired Spinoza’s God, “who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists,” not the personal deity of scripture.

This worldview grounded his ethics. To him, morality did not require divine command; it was a product of empathy, education, and reflection. “A human being,” he wrote, “is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings, as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness.”

His sense of wonder was also political. It led him to defend freedom of thought, racial equality, and social justice. When African-American singer Marian Anderson was denied lodging by segregated hotels in Princeton, Einstein invited her to stay in his home. He called racism “America’s worst disease.” His friendships with W. E. B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson were grounded in shared humanism.

Einstein’s pacifism, humanitarianism, and disdain for hierarchy made him both admired and misunderstood. To conservatives, he was naïve; to radicals, inconsistent. But he remained steadfastly independent — a man guided not by ideology but by conscience.

Love, imperfection, and the private man

Behind the myth of genius lay a more complicated human being. Einstein’s personal life was turbulent: two marriages, distant relationships with his children, and an inability to reconcile domestic routine with intellectual intensity. His first wife, Mileva Marić, a Serbian mathematician, collaborated on his early work but was later marginalised. Their separation was painful, and his letters reveal both tenderness and detachment.

He could be absent-minded, sometimes self-absorbed, yet capable of deep loyalty to friends. His humour remained disarming. “A clever person solves a problem,” he once quipped, “a wise person avoids it.” He played the violin daily, seeing music as a direct path to truth — “I live my daydreams in music,” he wrote.

What distinguished Einstein was not moral perfection but moral awareness. He admitted weakness, doubt, and regret. “I am not a genius,” he said, “I am just passionately curious.” That curiosity extended to ethics as much as physics: a lifelong attempt to align inner conviction with outer action.

The public philosopher

After the war, Einstein became one of the world’s most recognisable figures. His image — the wild hair, the pipe, the wry smile — became shorthand for genius itself. But he used his fame not for comfort but for advocacy. He spoke for civil liberties during the McCarthy era, supported Zionism as a cultural, not nationalist, project, and declined an offer to become Israel’s second president, saying he lacked “the natural aptitude and experience to deal properly with people.”

He advocated disarmament, education, and scientific cooperation. His letters to contemporaries such as Sigmund Freud, Bertrand Russell, and Rabindranath Tagore reveal a restless mind seeking moral clarity. In his correspondence with Freud, Why War?, Einstein explored the psychological roots of violence, concluding that only a supranational authority could prevent humanity from destroying itself.

When accused of being unpatriotic, he replied simply: “My country is the world, and my religion is to do good.” His was not a utopian faith but a pragmatic hope — the belief that reason and empathy, properly cultivated, could offset humanity’s darker instincts.

Science as moral imagination

Einstein’s scientific vision and ethical outlook were two sides of the same coin. Relativity itself arose from a desire for coherence and fairness — a universe without privileged observers. Just as no frame of reference is absolute in physics, he believed no individual or nation holds moral absolutes. “Relativity,” he joked, “applies to physics, not ethics,” but the metaphor lingered: humility before truth, and suspicion of dogma.

He saw creativity as an act of moral courage — the willingness to question accepted wisdom. “Imagination is more important than knowledge,” he famously said, “for knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world.” Yet he never romanticised intellect detached from compassion. “The true value of a human being,” he wrote, “is determined by the measure and the sense in which he has attained liberation from the self.”

For Einstein, science was a dialogue with mystery. The laws of nature were not weapons of mastery but invitations to wonder. His lifelong quest for a unified field theory — a single framework encompassing all forces — reflected his yearning for moral as well as physical unity. He never completed it, but perhaps that incompleteness was the point: the universe, like conscience, resists finality.

Final years and enduring legacy

In his later years, Einstein lived modestly in Princeton, refusing most honours and avoiding celebrity excess. He bicycled around town, entertained visitors with dry jokes, and kept a small group of close friends. He wrote, lectured, and continued to correspond with scientists, philosophers, and politicians worldwide.

When he died in 1955, aged seventy-six, he left instructions that his body be cremated and his ashes scattered secretly, so no shrine could form around his remains. His brain, however, was removed by the pathologist — without permission — and studied for decades, a macabre symbol of humanity’s fascination with genius.

Today, Einstein endures as both scientific pioneer and moral compass. His equations underpin technologies from GPS to nuclear energy, yet his ethical warnings feel more urgent than ever. In an era of artificial intelligence, genetic editing, and escalating militarism, his insistence that science must serve conscience remains prophetic.

He once wrote to a friend: “Try not to become a man of success, but rather try to become a man of value.” That simple injunction, grounded in a life of exile, doubt, and integrity, may be his greatest contribution.

The meaning of Einstein today

Einstein’s legacy is not frozen in history. Each generation rediscovers him through its own anxieties — as the refugee who spoke for displaced people, the scientist who foresaw climate and nuclear peril, the rebel who valued thought over conformity. His life reminds us that intellect divorced from empathy is perilous, and that moral courage is itself a form of genius.

He believed that progress depended not only on scientific breakthroughs but on moral evolution — a shift in consciousness. “Peace cannot be kept by force,” he said, “it can only be achieved by understanding.” In that sentence lies the bridge between physics and ethics, between relativity and responsibility.

To study Einstein, then, is to confront the question he lived by: how should we use knowledge? His answer, implicit in every lecture, letter, and protest, was that understanding the universe is meaningless unless we also learn to understand ourselves.

Newshub Editorial in Europe – 9 November 2025

Recent Comments