A new global health study has warned that looming cuts to anti-malaria funding could reverse decades of progress and trigger the deadliest resurgence of the disease in modern history. The research, led by the Global Health Policy Institute, suggests that reduced contributions from high-income countries could result in millions of additional deaths and vast economic losses across Africa and Southeast Asia.

A crisis of funding and momentum

According to the report, international commitments to combat malaria are expected to fall by nearly 30% over the next three years as donor nations redirect budgets towards domestic spending and other global crises. Programmes supported by the Global Fund, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation could face shortfalls exceeding $1.2 billion by 2027.

The study estimates that every $100 million reduction in annual malaria funding could lead to an additional 160,000 deaths per year, mostly among children under five. Researchers warn that unless alternative financing is secured, infection rates could surge to levels not seen since the early 2000s, when malaria killed more than a million people annually.

Progress under threat

Over the past two decades, coordinated efforts across Africa and Asia have halved malaria mortality rates through a combination of insecticide-treated bed nets, rapid diagnostic tests and improved access to antimalarial drugs. These gains, the report cautions, are now at risk of collapsing.

Several frontline nations — including Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tanzania and Mozambique — have already reported shortages of bed nets and medication. In Southeast Asia, renewed resistance to artemisinin-based treatments is compounding the threat.

Dr. Laila Omondi, an epidemiologist in Nairobi who contributed to the study, said: “If these cuts proceed, we will see a generation of progress wiped out. Malaria is preventable and treatable, yet without sustained funding, it will once again become a leading cause of death in low-income countries.”

Economic and social impact

Beyond the human toll, the study highlights the wider economic cost. A resurgence in malaria could drain as much as $12 billion annually from African economies through lost productivity, reduced tourism and higher healthcare expenses. The researchers also note that falling investment in vector-control infrastructure may undermine preparedness for other mosquito-borne diseases, including dengue and Zika.

Health economists emphasise that preventing malaria remains one of the most cost-effective global interventions — every dollar spent is estimated to return up to $40 in economic benefits. “Cutting funding now is not saving money,” said the report’s lead author. “It’s deferring an even greater cost in lives and lost growth.”

A call for renewed global commitment

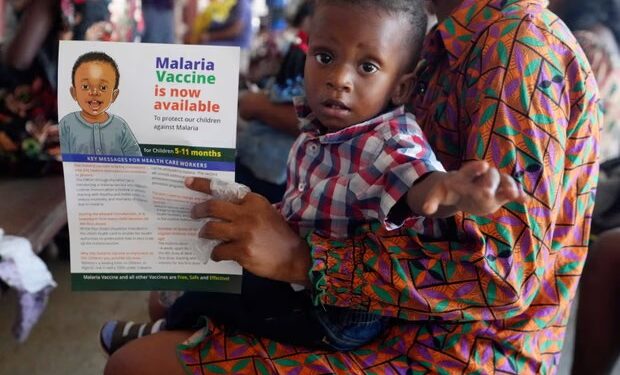

The authors urge donor governments and private-sector partners to recommit to malaria eradication targets, warning that failure to act could undo a generation of health gains. They recommend establishing a replenishment mechanism to stabilise funding and accelerate vaccine rollout, particularly for the newly approved RTS,S and R21 malaria vaccines.

With the World Malaria Report due later this year, public health advocates hope the findings will serve as a wake-up call to policymakers. Without immediate action, experts warn, the world could face the deadliest resurgence of malaria in living memory — a crisis both foreseeable and preventable.

Newshub Editorial in Africa – 21 October 2025

Recent Comments