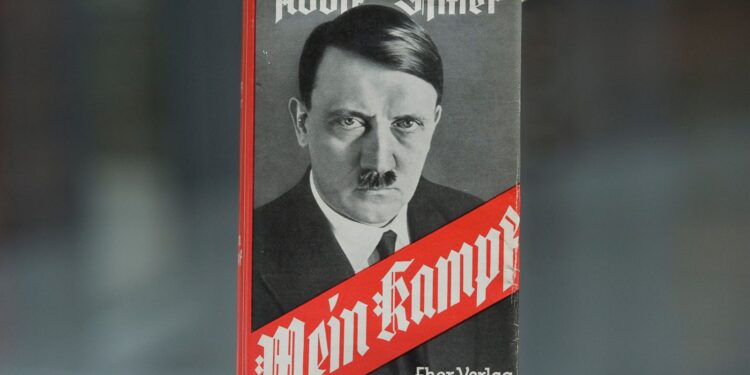

The publication history of Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler’s political manifesto, remains one of the most controversial and studied aspects of twentieth-century publishing. Since its first release in 1925, the book has represented a deep ethical challenge, balancing freedom of expression with the duty to prevent hate, incitement and historical denial.

Origins and initial impact

Mein Kampf (translated as My Struggle) was written by Hitler while imprisoned following the failed Beer Hall Putsch in 1923. It laid out his extreme nationalist, racist, and antisemitic ideology, including visions of German expansion and the destruction of so-called “undesirable” elements of society. Upon Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, the book became mandatory reading in Nazi Germany, distributed widely and generating substantial revenue for its author.

By the end of the Second World War, more than 12 million copies had been printed in German alone. The book’s role in shaping and spreading Nazi ideology made it a central piece of the propaganda machine.

Post-war restrictions and legal barriers

Following Germany’s defeat in 1945, Allied occupation authorities banned the publication of Mein Kampf in Germany and Austria. The copyright was transferred to the Bavarian government, which refused to allow any new editions, aiming to suppress its influence. The book, however, remained available in various unauthorised editions abroad, particularly in the United States, the Middle East, and parts of South Asia.

Germany’s post-war laws against Holocaust denial and hate speech further complicated the question of republication, especially as debates intensified over historical education versus censorship.

Reappearance and annotated editions

In 2016, after the copyright expired 70 years after Hitler’s death, the Munich-based Institute for Contemporary History published a heavily annotated academic edition. This version sought to contextualise Hitler’s claims, expose the fallacies, and provide a critical framework for understanding the work without endorsing it. Despite protests, the publication was praised by historians and educators for removing the taboo and allowing scholarly confrontation of the text’s dangers.

The annotated edition sold out rapidly, indicating strong interest from the public, academics, and teachers—not in the ideology, but in its dissection. The institute emphasised the work as a tool for prevention, not promotion.

A symbol of vigilance, not a source of revival

Today, Mein Kampf remains a symbol of the catastrophic consequences of political extremism, propaganda, and state-sponsored hatred. While it is legally available in many countries, its presence is monitored, and educational uses are encouraged over general circulation. In Germany, schools rarely reference the text directly, but its ideas are explored within the wider context of Holocaust education and democratic values.

The legacy of Mein Kampf is not merely the text itself but the collective effort to understand, critique, and ensure that its worldview is never again translated into policy or practice.

REFH – Newshub, 18 July 2025

Recent Comments