On the night of June 17, 1972, five men attempted what seemed like an ordinary burglary at the Watergate Office Complex in Washington, D.C. What they could not have anticipated was that their arrest would trigger the most significant political scandal in American history, ultimately bringing down a presidency and forever changing how Americans viewed their government.

The Crime That Started It All

At approximately 2:30 AM, security guard Frank Wills discovered tape covering the locks on several doors in the Watergate complex. After removing the tape and finding it replaced during his next round, Wills called the police. Officers arrived to find five men inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters on the sixth floor, equipped with sophisticated surveillance equipment, cameras, and large amounts of cash.

The burglars were James McCord, Virgilio González, Bernard Barker, Eugenio Martínez, and Frank Sturgis. McCord, notably, was the security coordinator for President Nixon’s re-election campaign, the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CRP), often mockingly called “CREEP” by critics.

Initial Cover-Up Attempts

The Nixon administration immediately distanced itself from the break-in. Press Secretary Ron Ziegler dismissed it as a “third-rate burglary attempt,” and President Nixon himself denied any White House involvement. However, investigative reporting by Washington Post journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein began uncovering connections between the burglars and high-level Republican operatives.

The reporters discovered that one of the burglars carried an address book containing the phone number of E. Howard Hunt, a White House consultant and former CIA operative. This connection would prove to be the first thread that, when pulled, would unravel the entire conspiracy.

The Expanding Investigation

What began as a simple burglary investigation evolved into something far more complex. Federal prosecutors and congressional investigators discovered that the break-in was part of a broader campaign of political espionage and sabotage directed against the Democratic Party and other perceived enemies of the Nixon administration.

The investigation revealed that the Committee to Re-Elect the President had funded not only the Watergate operation but also other illegal activities, including wiretapping, break-ins, and the creation of fake documents designed to damage Democratic candidates. A secret fund, controlled by key Nixon advisors, had financed these operations.

Key Players and Connections

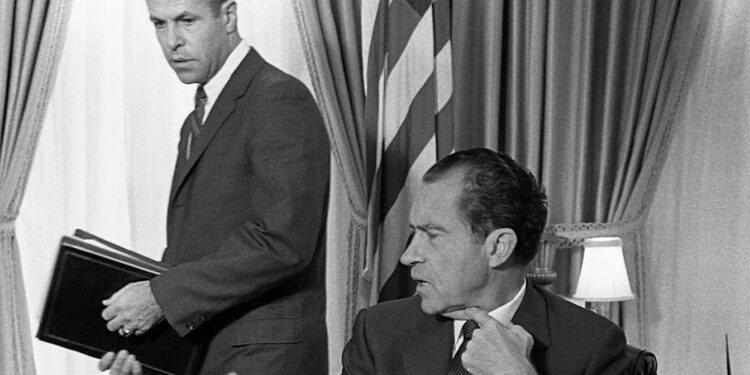

As the investigation deepened, it became clear that knowledge of these activities extended high into the Nixon administration. John Mitchell, the former Attorney General who had become Nixon’s campaign manager, was implicated in approving the operation. White House Counsel John Dean emerged as a central figure who had helped coordinate the cover-up efforts.

The investigation also revealed the existence of the White House “Plumbers,” a covert unit created to stop information leaks. This group, which included Hunt and G. Gordon Liddy, had previously broken into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, seeking damaging information about the man who had leaked the Pentagon Papers.

The Role of Deep Throat

Woodward and Bernstein’s investigation was aided by a mysterious source they called “Deep Throat,” who provided crucial guidance and confirmation of their findings through clandestine meetings in underground parking garages. This source remained anonymous for over three decades until former FBI Associate Director Mark Felt revealed himself as Deep Throat in 2005.

Congressional Hearings and the Smoking Gun

The Senate Watergate Committee, chaired by Sam Ervin, held televised hearings that captivated the nation during the summer of 1973. Americans watched as witnesses testified about abuse of power, illegal surveillance, and attempts to obstruct justice at the highest levels of government.

The most explosive revelation came from White House aide Alexander Butterfield, who disclosed that Nixon had secretly recorded most of his conversations in the Oval Office. These tapes became the focus of intense legal battles, with Nixon claiming executive privilege while prosecutors demanded access to evidence of potential crimes.

The Constitutional Crisis

Nixon’s refusal to release the tapes led to a constitutional crisis. When Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox insisted on obtaining the recordings, Nixon ordered his firing in what became known as the “Saturday Night Massacre.” Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus both resigned rather than carry out the order, leaving Solicitor General Robert Bork to dismiss Cox.

The Supreme Court ultimately ruled in United States v. Nixon that executive privilege could not be used to withhold evidence in criminal proceedings, forcing the president to release the recordings.

The Downfall

The released tapes contained the “smoking gun” evidence that proved Nixon’s direct involvement in the cover-up. A recording from June 23, 1972, just six days after the break-in, showed Nixon discussing how to use the CIA to impede the FBI’s investigation.

Facing certain impeachment and removal from office, Richard Nixon became the first U.S. president to resign, announcing his decision on August 8, 1974, and leaving office the following day.

Legacy and Impact

The Watergate scandal had profound and lasting effects on American politics and society. It led to significant reforms in campaign finance laws, government ethics rules, and congressional oversight procedures. The Freedom of Information Act was strengthened, and new protections were established for whistleblowers.

Perhaps most importantly, Watergate fundamentally altered the relationship between the American people and their government. The scandal shattered the notion of presidential infallibility and created a more skeptical, questioning press and public. The suffix “-gate” became permanently attached to political scandals, reflecting the enduring impact of those five men who broke into the Watergate complex on that June night in 1972.

The break-in that was supposed to give Nixon’s campaign an advantage in the 1972 election instead became the catalyst for the most significant constitutional crisis since the Civil War, proving that in America, no one, not even the President, is above the law.

newshub finance

Recent Comments