Two Swedish industrial spheres — the Wallenberg network and the Rausing family — quietly control capital measured in trillions of kronor, placing them among the world’s most influential private ownership groups even as they operate far from public attention. As markets reassess concentration of capital in 2026, their contrasting models offer a clear view of how power is structured in modern industry.

Two models of control

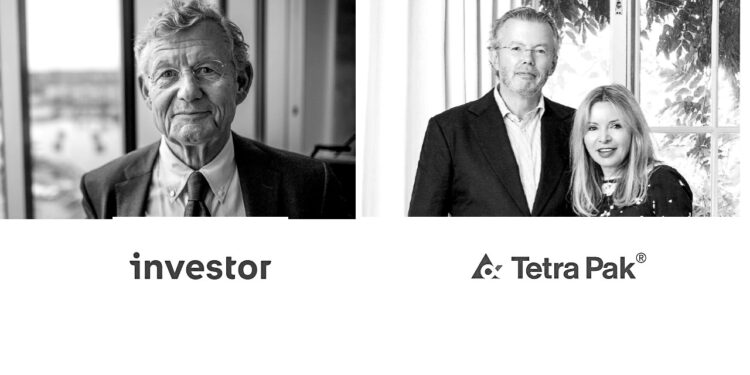

Sweden’s ownership landscape is dominated by two very different approaches. The Wallenberg sphere operates through foundations and listed holding companies, with control exercised primarily via Investor AB and FAM. This structure provides decisive voting power across a portfolio of globally active firms in engineering, banking, defence and telecoms.

By contrast, the Rausing sphere is built around a single privately held industrial champion: Tetra Pak. Owned by the Rausing family through private holding entities, the group remains almost entirely opaque, publishing limited financial detail while generating substantial cash flow from food packaging and processing systems sold worldwide.

The difference is stark: Wallenberg represents a diversified ecosystem; Rausing is a highly concentrated monolith.

How much capital is involved

Estimates based on current market values and ownership structures suggest that the Wallenberg sphere exerts strategic influence over industrial assets worth approximately SEK 2,500–3,000 billion. This reflects holdings and voting control across companies spanning automation, banking and advanced manufacturing.

Rausing-controlled assets are smaller in aggregate but unusually concentrated. Tetra Pak alone is widely estimated to represent SEK 1,200–1,500 billion in enterprise value when its global footprint, margins and adjacent activities are taken into account.

In practical terms, Wallenberg controls more total capital. Rausing controls one of the world’s most profitable private industrial businesses.

Global comparison puts Sweden on the map

Placed in a global context, both Swedish groups rank among the major private ownership spheres, though neither sits at the absolute top. The Waltons of Walmart and Bernard Arnault’s control of LVMH operate on a larger scale, while India’s conglomerates, led by Reliance Industries, rival Wallenberg in breadth.

Still, Sweden’s footprint is remarkable relative to its population size. Few countries of comparable scale host two ownership groups with sustained control over globally competitive industrial platforms.

Why structure matters for markets

The implications extend beyond national pride. Wallenberg’s model spreads risk across multiple sectors and relies on long-term stewardship through voting shares. It favours stability, incremental innovation and institutional continuity.

Rausing’s model maximises focus and operational efficiency, allowing rapid decision-making inside a tightly held private framework. That concentration delivers exceptional margins but offers little transparency to external stakeholders.

For investors and policymakers, the contrast illustrates two viable paths to scale: diversified public influence versus private industrial dominance.

A quiet form of power

Neither sphere seeks headlines. Yet together they shape supply chains, employment and capital flows far beyond Scandinavia. As global markets increasingly scrutinise ownership concentration, Sweden’s twin giants stand as case studies in how enduring control can be built — either through networks of listed companies or through a single, formidable private enterprise.

Newshub Editorial in Europe – 11 February 2026

If you have an account with ChatGPT you get deeper explanations,

background and context related to what you are reading.

Open an account:

Open an account

Recent Comments