After three voyages to the Americas, Christopher Columbus embarked on his fourth and final expedition in May 1502. By this time, the Spanish monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella had grown somewhat disillusioned with Columbus’s earlier promises of vast wealth. His previous voyages had not yielded the gold and spices he had forecast, and his administrative abilities had been called into question during his governance of Hispaniola.

Nevertheless, the Spanish Crown authorized this final voyage with limited objectives: to find a westward passage to Asia and to explore new territories that might yield profitable resources. Columbus was explicitly forbidden from visiting Hispaniola, where he had previously been governor but was now unwelcome due to his controversial leadership.

The aging explorer, now approximately 51 years old, prepared a fleet of four vessels: the flagship Capitana, along with Santiago de Palos, Vizcaíno, and Gallega. He brought along his younger brother Bartholomew and his 13-year-old son Ferdinand, who would later document the journey.

The Expedition Begins

The fleet departed from Cádiz, Spain on May 9, 1502, with approximately 140 men. Despite the royal prohibition, Columbus’s first major decision was to head directly to Santo Domingo in Hispaniola when he arrived in the Caribbean. He claimed this was necessary to replace one of his ships, but it was also likely a deliberate challenge to his replacement as governor, Nicolás de Ovando.

Approaching Hispaniola in late June, Columbus recognized signs of an impending hurricane and requested permission to shelter in the harbor of Santo Domingo. Governor Ovando refused his entry, perhaps out of political animosity. Columbus then warned the harbor officials about the coming storm and sought shelter elsewhere along the island’s coast.

Ironically, a treasure fleet of about 30 ships departed Santo Domingo for Spain despite Columbus’s warning. The hurricane struck with devastating force, sinking many vessels of that fleet, including the ship carrying Bobadilla, the man who had previously arrested Columbus and sent him back to Spain in chains after his third voyage. Columbus’s small fleet, meanwhile, weathered the storm with minimal damage.

Exploring Central America

After the storm passed, Columbus continued westward, reaching Guanaja Island (off the coast of present-day Honduras) by the end of July. From there, he sailed along the Central American coast, exploring what is now Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama.

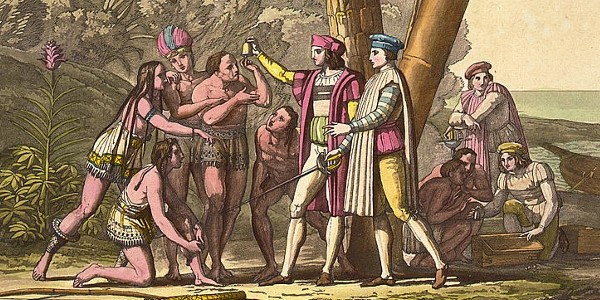

During this segment of the journey, Columbus encountered the most sophisticated indigenous civilizations he had yet seen in the New World. The Maya of this region had developed advanced agricultural techniques, complex political systems, and elaborate trade networks. Columbus was particularly impressed by their gold ornaments, which reinforced his belief that he was approaching the wealthier regions of Asia.

In early January 1503, Columbus established a small settlement called Santa María de Belén in what is now Panama. He believed he was close to finding a passage to the Indian Ocean. Gold found in nearby rivers convinced him that this was part of the legendary gold-producing region of Veragua, mentioned in earlier accounts of Asia.

Disaster and Stranding

The expedition’s fortunes soon took a severe downturn. Relations with the indigenous peoples deteriorated rapidly. The local cacique (chief) Quibián launched attacks against the Spanish settlement, forcing its abandonment. One of Columbus’s ships had to be left behind due to wood-boring shipworms that had damaged the hull beyond repair.

As the remaining three vessels attempted to leave the area, another ship had to be abandoned due to similar damage. The crews consolidated onto the two remaining vessels, which were now overcrowded and in poor condition. By June 1503, the ships were taking on water faster than the crews could bail. Columbus made the critical decision to beach the failing vessels on the northern coast of Jamaica at a place he named Santa Gloria (now St. Ann’s Bay).

Stranded in Jamaica

For an entire year, from June 1503 to June 1504, Columbus and his crews remained stranded on Jamaica. During this time, they faced multiple challenges:

- Dwindling supplies and food shortages

- Deteriorating health conditions, particularly scurvy

- Increasingly hostile relations with the indigenous Arawak people

- A mutiny led by the Porras brothers among half of the remaining crew

One of the most famous episodes of this period was Columbus’s prediction of a lunar eclipse. Using his astronomical knowledge and an almanac, Columbus informed the initially generous but increasingly reluctant Arawak chiefs that his god would take away the moon as a sign of displeasure if they stopped providing food to the Spaniards. When the eclipse occurred as predicted on February 29, 1504, the Arawak, impressed by what they perceived as supernatural power, resumed trading food with the stranded explorers.

Rescue and Return

Columbus had dispatched his loyal captain Diego Méndez in a native canoe to reach Hispaniola and arrange rescue. After an arduous journey and multiple attempts, Méndez reached Santo Domingo. However, Governor Ovando deliberately delayed sending help, perhaps hoping Columbus would perish.

Finally, in June 1504, a rescue vessel chartered by Columbus’s agent arrived at Jamaica. By this time, half of Columbus’s original crew had died, and many others were ill. The survivors reached Hispaniola in August 1504 and departed for Spain on September 12.

Columbus arrived back in Spain on November 7, 1504, physically broken and in poor health. Queen Isabella, his primary royal supporter, died just three weeks later.

Legacy of the Fourth Voyage

Despite its hardships, the fourth voyage produced significant geographical knowledge:

- It confirmed that there was no direct sea passage through Central America to Asia

- It expanded Spanish knowledge of the Central American coast and its indigenous peoples

- It provided the first European contact with the mainland of Central America

- It contributed to the growing understanding that Columbus had not reached Asia but had instead found a “New World”

The journey also revealed Columbus’s remarkable tenacity and navigational skills under adverse conditions. Even as his body failed him, suffering from arthritis, eye infections, and possibly malaria, he maintained enough command to ensure that at least some of his crew survived the ordeal.

Despite these achievements, the fourth voyage represented a personal defeat for Columbus. He never found the westward passage to Asia that had been his lifelong goal. He failed to secure the restoration of his privileges and titles that had been stripped after his third voyage. And he returned without the wealth that he had repeatedly promised to the Spanish Crown.

Final Years

After his return, Columbus spent his final years in declining health, fighting legal battles to restore his titles and privileges. He died in Valladolid, Spain on May 20, 1506, at the age of 54. The man who had once been celebrated as the “Admiral of the Ocean Sea” passed away without fully realizing how profoundly his voyages had changed world history.

The fourth voyage, perhaps more than any other, reveals the complex character of Columbus: stubborn, visionary, skilled yet flawed, capable of both genuine exploration and self-deception. While his legacy remains deeply contested, the fourth voyage stands as a testament to both human determination and the high cost of colonial ambitions.

Recent Comments