On October 24, 1929, the United States stock market suffered an unprecedented collapse that would mark the beginning of the Great Depression and fundamentally reshape American economic policy for decades to come. Known as “Black Thursday,” followed by the even more devastating “Black Tuesday” on October 29, these events brought a dramatic end to the prosperous “Roaring Twenties” and ushered in an era of economic hardship.

The 1920s had been characterized by extraordinary economic growth and speculation. Stock prices had risen nearly 400% over the decade, fueled by easy credit, margin buying, and unbridled optimism about the American economy. Ordinary citizens, many with no prior investment experience, rushed to put their savings into stocks, often borrowing heavily to do so. By 1929, the stock market had become a symbol of seemingly endless prosperity.

However, beneath the surface, dangerous economic indicators were emerging. Agricultural prices had been declining throughout the decade, and consumer debt had risen dramatically. The gap between rich and poor had widened substantially, with the top 0.1% of Americans controlling 34% of all savings. Market manipulation and insider trading, which were still legal, contributed to artificial inflation of stock prices.

The first signs of the impending crash appeared in September 1929, when stock prices began to fluctuate wildly. The real crisis began on October 24, when nearly 13 million shares changed hands on the New York Stock Exchange – a record that would stand for nearly 40 years. Leading bankers attempted to stabilize the market by buying large blocks of stocks, providing temporary relief.

However, the worst was yet to come. On Tuesday, October 29, more than 16 million shares were traded in a single day. Stock prices collapsed completely, with some companies’ shares becoming utterly worthless. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 38 points to 260, a drop of 13%. Over the next two weeks, the market lost 40% of its value. By 1932, stocks would be worth only about 20% of their value in 1929.

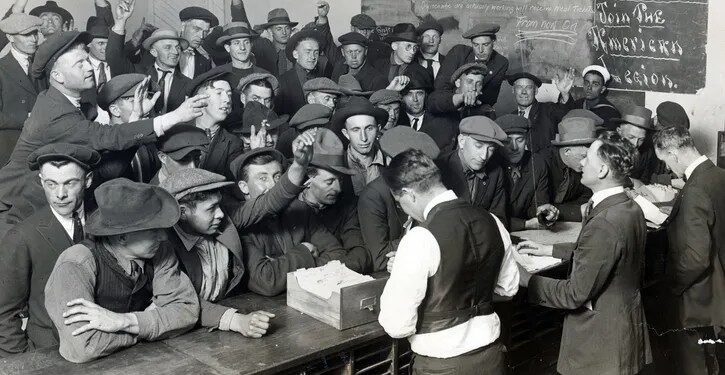

The crash had devastating consequences. Bank failures became common as customers rushed to withdraw their savings. Between 1929 and 1933, nearly half of America’s banks failed. The banking crisis spread from the United States to Europe, making the economic disaster an international phenomenon. Unemployment in the United States rose from 3.2% in 1929 to 24.9% in 1933, with similar increases in other industrialized countries.

The crash exposed fundamental weaknesses in the American financial system. There had been no federal regulation of the stock market, no protection for bank deposits, and no federal insurance of bank accounts. The Federal Reserve, established in 1913, had failed to prevent the speculation that led to the crash or to take effective action to mitigate its effects.

The disaster led to significant reforms under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Securities and Exchange Commission was created to regulate the stock market. The Glass-Steagall Act separated commercial and investment banking. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was established to protect bank deposits.

The 1929 crash remains the most severe stock market crash in American history and serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of speculation and inadequate financial regulation. Its effects transformed not only the American economy but also American society and politics. The experience of the crash and subsequent Depression shaped the outlook of a generation and influenced economic policy for the remainder of the 20th century.

The lessons of 1929 continue to resonate today, particularly during periods of rapid market growth and financial innovation. While modern safeguards make an exact repeat of 1929 unlikely, the fundamental insights about the importance of market regulation, the dangers of excessive speculation, and the need for consumer protection remain relevant to contemporary financial markets.

newshub

Recent Comments