For years the frontman couldn’t enjoy the rock star ride – and now that he finally is, a vocal injury could end it. He explains how he stays upbeat, even with the US at a precipice’

In 1982, Jon Bon Jovi recorded a song called Runaway during his downtime while working at a New York recording studio. Every record company he approached rejected it, but a radio DJ encouraged him to enter an unsigned band competition, which he won. Not long after, Bon Jovi was driving back to his parent’s house in Sayreville, New Jersey. “I was alone in the car and I heard Runaway on the radio for the first time,” he recalls. “I wanted to roll the windows down and drive fast – I hoped that I would get pulled over just so I could tell the cops that was me on the radio.”

Alone and driving fast with the radio on: it could be a Bon Jovi lyric. And 42 years, 16 studio albums and millions of sales later, the journey that started with Runaway now reaches a new album Forever. As on the band’s recent documentary series, Thank You, Goodnight, it’s Jon Bon Jovi looking in the rearview mirror: one song is about buying his first guitar, while another revisits the band’s days playing on the Jersey shore. But those early gigs built up into a career that he now realises he often wasn’t allowing himself to enjoy. “I was competing with myself for a long period,” he says.

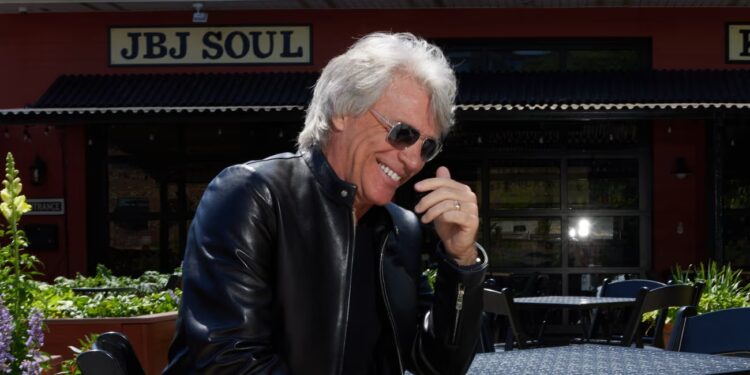

We’re talking at Soul Kitchen in Red Bank, New Jersey, a nonprofit, pay-what-you-can restaurant for low-income families that Bon Jovi set up with his wife, Dorothea. It’s two minutes’ walk from the Count Basie theatre where Bon Jovi played a string of Christmas shows in the 90s, and a seven-minute drive from where Bon Jovi now lives. Sayreville, where he grew up, is 35 minutes north-west. “All of our values were established here,” he says. “No matter how far you go, you carry your home town with you.”

He sounds as if he is sharing an earlier draft of a line from the new album – “I know this town like the back of my hand / Every crack in the sidewalk tells me who I am” – but, understandably, he’s taking stock. Now 62, Bon Jovi is not just looking back at his home life – including a marriage that has lasted 35 years – but his life’s work. A cruel irony is that after finally learning to enjoy that career, it’s under threat from a damaged vocal cord, making the prospect of future touring unlikely. “It’s a work in progress,” he says of his voice. “There’s no miracle. I just wish there was a fucking light switch. I’m more than capable of singing again. The bar is now: can I do two and a half hours a night, four nights a week? The answer is no.”

Bon Jovi grew up the son of a florist father and a mother who joined the Marines after having been a Playboy bunny. “Your typical middle-class upbringing,” as he has it. “It was very much a blue-collar childhood. No one I was best friends with or even buddies with were seeking higher education. It was the factory or the service.” Bon Jovi was given an electric guitar as a Christmas present aged 13, and his bedroom was plastered with posters of musical heroes. “When you’re that age everybody thinks you’re gonna be a rock’n’roll star and that you’re gonna make it,” he says, “I was just dumb enough to believe it.”

What made “the impossible possible” was that not far from where he lived, another New Jersey musician had made it. “I first went to see Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band in 1978,” he recalls. “They were 30 miles south of my bedroom, writing songs about the places that I lived. And unlike the people on the posters on my wall – Led Zeppelin and Queen and Elton John – you could walk into a bar in New Jersey and run into Bruce or one of the band.”

On 9 January 1980 Bon Jovi was performing at the Fast Lane, a venue in Asbury Park, with his band Atlantic City Expressway. He was halfway through a cover version of Springsteen’s The Promised Land when he turned around to see Springsteen, who had been in the audience and was now about to join him on stage. “That was magical. Remember: I am going back to high school the next day.” Later that year a cousin helped Bon Jovi get a lowly job at the Power Station recording studio in New York, where he ran errands. He was still a teenager but able to watch the likes of Mick Jagger, Diana Ross and Dire Straits at work, plus Queen and David Bowie recording Under Pressure. When the studio was not being used, Bon Jovi would use it to record his own music, including Runaway.

Bon Jovi released two moderately successful albums before going supersonic with 1986’s Slippery When Wet. What if he hadn’t had that cousin who worked at the Power Station? “It was gonna happen,” he says. “I would’ve recorded Runaway somewhere else. I had the song.” He was certain he’d be successful. “There was no question, not even a moment of doubt. None.”

Slippery When Wet was stuffed with classics such as You Give Love a Bad Name, Wanted Dead Or Alive and Livin’ On a Prayer. Tommy and Gina, the couple in the latter song, were inspired by real people Bon Jovi knew who married young. “He sacrificed what would have been career choices for love, and I was astounded because I admired that sacrifice.” He laughs when I ask whether Tommy and Gina would now be Trump supporters, but admits to feeling nervous about the upcoming election. His new song The People’s House is about the January 6 insurrection. “Democracy is at stake: we are at a precipice in this country.”

Slippery When Wet made the band rich and famous and installed Bon Jovi as New Jersey royalty alongside Springsteen, the one person he could not face meeting was the state’s biggest musical name, Frank Sinatra. “That is one of my few regrets in life,” he says. “I had numerous chances but I wasn’t emotionally ready. I didn’t know enough about all the aspects of who he was and how so many of those aspects influenced things that I did in my life.” I jokingly say that Sinatra must have hated him for the repeated rebuffing, but it lands badly. “Why would you assume that?” Bon Jovi says, the air in the Soul Kitchen suddenly chilling. “Don’t write one of those stupid fucking English articles,” I repeat that it was just a joke. “I don’t believe you at all, but, OK, we’ll go with that,” he says, adding: “Don’t insult Frank.” I feel like an underling in front of a mob boss, but relations thankfully soon thaw.

Bon Jovi was disoriented by the success of Slippery When Wet. “It changed people around us more than it changed us,” he says. “Suddenly people who we would usually ask for advice” – such as his parents – “were now asking us for advice.” The rest of the band embraced the sex, drugs and rock’n’roll lifestyle, “but for me when everything relies on me singing, I’m going to have to go to bed earlier than the others. I wish I had enjoyed the success more, but somebody has to be the quarterback of the team to keep the band together.”

That success at least freed him and Dorothea to strike across the US in the late 80s, riding motorbikes, “staying in cheap motels – a beautiful way to see the country”. How did motel receptionists react when Jon Bon Jovi walked in? “I remember pulling into a gas station by the Grand Canyon and there was a kid who had one of our T-shirts on. I was like, hey. And he was like, hey. He didn’t recognise me. [In the end] I took off my helmet and pulled out my licence. I guess I didn’t look very good that day.”

Also keeping him grounded was Dorothea herself, and this year they celebrate 35 years of marriage. “I just got it right the first time,” he says. “I was blessed to have known her since we were kids and I couldn’t have ever imagined life any differently.” In the days before our meeting another interview goes viral, with Bon Jovi saying he “got away with murder” regarding women: “I’m a rock’n’roll star. I’m not a saint. I’m not saying that there weren’t 100 girls in my life. I’m Jon Bon Jovi. It was pretty good.” I barely start to mention it when he leaps in. “That was an interesting moment where the brain and lips don’t connect,” he says. “What I meant to say was I’ve had a hundred women who have thrown themselves at me, but I didn’t finish the sentence so I really came off like an arrogant cliche.”

While not entirely immune to rock star cliche – his teeth are blindingly white and he is fond of dispensing aphorisms that resemble insight – Bon Jovi is serious and thoughtful. He arrives with no entourage and pauses to thank the photoshoot’s makeup guy. He has devoted time and money to philanthropy, funding a health clinic for the poor, and housing for low-income families in Philadelphia. He has established four Soul Kitchen outlets across New Jersey and during the Covid pandemic, he spent his days washing dishes at the restaurant. “Connecting with somebody here is honest to God just as fulfilling [as playing live] because you know that they had a sense of community, and a place to come that was safe,” he says.

Kiss the Bride, from the new record, is about the wedding of his daughter, Stephanie, while his son Jake recently married the actor Millie Bobby Brown. I wonder, given his wealth, about the challenge of keeping them rooted, too. “You have kids,” he replies. “What do you do about it?” Bon Jovi is sometimes prone to deflection; I laugh and tell him we don’t have the same problem, but he genuinely seems interested in hearing about my parenting style. “My kids observe my work ethic and that’s in their DNA now – they’re not trust-fund babies,” he says eventually. “You have to go to work. I will give them enough to make sure they have shoes on their feet but like Dorothea says: ‘Daddy has money, you don’t have anything.’”

And regarding his vocal issues, Bon Jovi is determinedly buoyant, even if touring is off the table. His voice sounds great on the new album, and a few days earlier he had performed on American Idol: “It lights you up when you’re out there,” he says. “As long as I have the ability, I will write songs and make records.”

When he was young and on the start of his journey trying to hawk his first single around record labels and radio stations, Bon Jovi was driven, he says, by “youth, naivety and self-belief”. Four decades on, on the new song Living Proof, he’s singing that he’s “got nothing left to prove”, and he is clearly proud of Forever. “It feels very personal to me,” he says, calling it “the best album we have made in 20 years”.

The person who was always competing with himself is, he adds, “now absolutely where I want to be. I used to want to seize the day – now I just want to embrace the day.” He gets up, slips on his sunglasses, steps into a black sports car and takes the seven-minute journey back home.

Source: The Guardian

Recent Comments