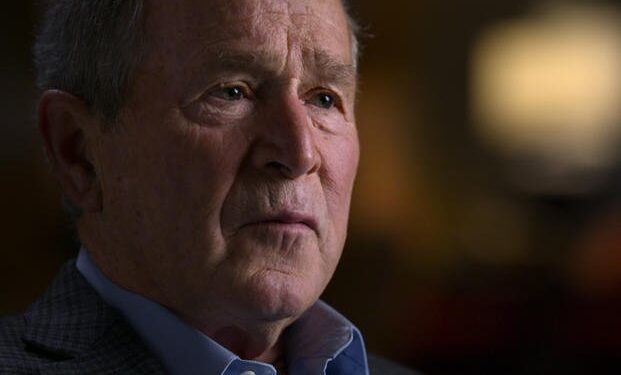

n April 29, 2004, President George W. Bush hosted one of the most unusual meetings to ever take place inside the Oval Office. The 10 members of the 9/11 Commission got to ask him and Vice President Dick Cheney any question they wanted about the September 11, 2001, attacks. The words that were spoken in that room remained secret for nearly two decades. Now, we can finally read what Bush said.

Earlier this month, after more than 18 years, the government declassified a 31-page “memorandum for the record,” which compiles notes that the commissioners took during the meeting. The document shows the commissioners giving Bush multiple chances to acknowledge the numerous documented warnings he’d received from his own government of an impending attack by Al Qaeda. For the most part, Bush failed to do so. Instead, he passed the buck.

Perhaps the largest of Bush’s evasions that day concerned his CIA director, George Tenet: “The threat was overseas — that was what George said.” Bush’s implication at the time is clear. He wanted the commission, and by extension the public, to think that no one could have anticipated Al Qaeda mounting a large-scale attack on US soil. But in fact, Tenet’s CIA had warned Bush more than once that Al Qaeda could strike anywhere, at any time, and that all US citizens were potential targets. The most notorious warning that Bush received, but not the only one, was a CIA briefing headlined “Bin Ladin Determined to Strike in US.”

Very little of Bush’s excuse-making and clumsy attempts to rewrite history found their way into the 9/11 Commission’s report. Indeed, one of the commissioners, Richard Ben-Veniste, told Insider he still had questions today about what Bush knew, and when.

“I could never square in my mind CIA Director Tenet’s intense preoccupation with the Al Qaeda threat in the months leading up to 9/11, with his claim that he never briefed President Bush on the many clues the intelligence community had developed that bin Laden was planning to launch a ‘spectacular’ attack on the US homeland,” Ben-Veniste said.

The commission report’s approach to this mystery is to make the apparent disconnect between CIA and the Oval Office sound like something out of a Greek tragedy: “No one working on these late [Al Qaeda] leads in the summer of 2001 connected them to the high level of threat reporting … no analytic work foresaw the lightning that could connect the thundercloud to the ground.”

What the new memo makes clear is that the White House’s lack of urgency in facing down the domestic Qaeda threat wasn’t all that complicated. Tenet, the record shows, did everything he could to get Bush to focus on Al Qaeda. Bush just wasn’t interested.

Not only was the Oval Office exchange an extraordinarily sensitive conversation, but it was happening at a perilous moment for Bush, who was gearing up to run for a second term. The commission was close to finishing its written report, which would be released to the public in July, less than four months before the election. That may be why Bush repeatedly waved aside suggestions that the meeting needed to wrap up. “It’s my Oval Office,” Bush said, when a commissioner suggested that a colleague keep things moving along. “Go ahead.” He continued to answer their questions for more than three hours.

If you want to understand how Bush escaped blame for 9/11, winning a second term despite having presided over one of the gravest and most costly failures in presidential history, you need to understand exactly what happened that day in the Oval Office almost 20 years ago.

The White House had negotiated for a joint meeting where Bush and Cheney would sit and answer questions together. But Bush didn’t lean too heavily on this accommodation. “The president was well-briefed and answered our questions fully,” one of the 9/11 commissions, former Gov. Thomas H. Kean of New Jersey, told Insider. “The President’s demeanor throughout was relaxed,” notes the memo. “He answered questions without notes.”

Bush didn’t respond to a request for comment. Quotes attributed to Bush in this story are taken from the memo, which is not a verbatim transcript and so should not be read as capturing Bush’s statements word for word.

Two weeks before the committee’s Oval Office meeting, the commission had heard from Tenet. His public testimony raised more questions than it answered — especially about what Bush knew and when. In the spring and summer of 2001, Tenet had warned Bush no fewer than 40 separate times that a major attack by Al Qaeda was on the horizon. Analysts called the flood of warnings a “threat spike” and the “summer of threat.”

Nevertheless, Bush chose to spend most of August at his ranch in Crawford, Texas, on a “working vacation.” Shortly after arriving, on August 6, he’d received the detailed President’s Daily Brief from the CIA, with its direct warning that bin Laden intended to strike inside the US. By 2004, after that PDB became public, commentators were taking seriously the possibility that Bush had one job — keep the country safe — and that he’d failed to do it.

“If only Osama had faxed an X-marks-the-spot map to the Crawford ranch showing the Pentagon, the Capitol, the twin towers and the word ‘BOOM!’ scrawled in Arabic,” wrote Maureen Dowd, the New York Times opinion columnist, at the time. “That might have sparked sluggish imaginations. Or maybe not.”

Fortunately for Bush, the 9/11 Commission Report was careful not to point the finger directly at the sitting president. While the report acknowledges the August 6 PDB, headlined “Bin Ladin Determined to Strike in US,” it states unequivocally that there is “no indication of any further discussion” by Bush and his team regarding a domestic terrorist attack. Reading the commission’s report, one can see a torrent of warnings coming out of the CIA and a sense of growing alarm among Bush’s counterterrorism team. But the failure of those loud and repeated warnings to reach Bush’s brain is attributed mainly to institutional problems, issues with “imagination, policy, capabilities, and management.”

Unlike Dowd, the commission chose not to question Bush’s competence. “We chose not to assign individual responsibility for the failure to prevent 9/11,” Ben-Veniste, the former 9/11 commissioner, said. “But rather to lay out the facts we had uncovered and allow the public, and ultimately history, to make judgments based on that factual record. At the same time, we used our unanimity of purpose to prioritize our objective of getting Congress to enact our recommendations to make the country safer.”

It’s worth considering whether going after Bush directly was even a real option for the commission, given its bipartisan mandate and the looming presidential election. Still, when set beside the newly declassified memo, their official version of history as described by the 9/11 Commission Report feels incomplete and sanitized. What’s missing from the report and captured by the new memo is Bush’s defensiveness, and his persistent attempts to minimize the warnings he got from Tenet and the CIA.

“It shouldn’t have stayed secret for so long,” Kean, the former New Jersey governor and 9/11 commissioner, told me. “We want everything out in the public record.”

On the question of pre-9/11 warnings, Bush stuck to a few points:

First, according to Bush, the Qaeda threat, as it was presented to him, was almost exclusively “overseas.”

He [Bush] explained how these conversations went. [George] Tenet [Bush’s CIA director] would come in: Mr. President, we have a serious threat. He would describe it. The President would turn to him and others and say: What are you doing about it? That never happened (for a threat in the United States). No one said there was a problem domestically. The threat was overseas — that was what George [Tenet] said.

Second, to the extent that Al Qaeda posed a threat on US soil, Bush says that no one told him how, when, or where it would strike. There was, in his view, no “actionable intelligence,” not about Osama bin Laden, and not about Qaeda personnel on US soil. The August 6 briefing about bin Laden’s intentions, he said, “was historical in nature.” Other than that, Bush claimed, he had never been informed about the potential for an attack on the US. “There was no actionable intelligence on such a threat,” he told the commission. “Not one.”

Third, Bush didn’t think it was productive to assign responsibility for pre-9/11 failures to individuals. “It should not be about blaming people,” he said. “The country was ill served by playing the blame game … the President didn’t see much point in assigning personal blame for 9/11 … nobody wants to see something like this happen. They would have moved heaven and earth to stop it.”

Bush’s story hangs together on its own. It is also consistent with the commission’s final report, which drew heavily from the Oval Office interview. And there is some support in the public record for Bush’s claims about the vagueness of the pre-9/11 warnings that reached his desk, though some questions remain about what might not be public. One document that inexplicably remains classified is a 7,000-word report created for 9/11 commission members that describes in detail all of the pre-9/11 Qaeda warnings received by the Clinton and Bush administrations.

But aside from the specificity of pre-9/11 warnings, there is the question of whether Bush took the possibility of a domestic attack seriously, by stepping up security, or demanding additional details on domestic counterterrorism efforts from the CIA and the FBI. In the August 6 briefing, after all, Bush was told the FBI had no fewer than 70 active investigations related to bin Laden inside the US. In the Oval Office, Bush told the commissioners that he took the warning seriously and that if the FBI “found something” related to the 70 investigations, he “wanted to hear about it.”

On this point, a different narrative has emerged from the CIA over the years.

Consider the following statements made in a 2021 podcast by Michael Morell, Bush’s lead CIA briefer, who later went on to serve as the agency’s deputy director:

The CIA provided strategic warning of the AQ threat. In my view, this was arguably the loudest and most persistent warning in the history of the agency on any issue ever …

I strongly sensed during the spring and summer of 2001 that Tenet was deeply frustrated with the White House. I sensed that Tenet felt that the White House just did not get it. I think this is why he went to such lengths — taking over the briefing [of Bush] from me, taking his counterterrorism team to see [Condoleezza] Rice twice. I think he was trying anything he could to get their attention.

Tenet, Morell adds on the podcast, “repeatedly took his concerns to the highest levels of our government.”

So what exactly did Tenet say to Bush about Al Qaeda? From reading the account that Bush gave to the commissioners, you might conclude that Tenet had never raised the possibility that Al Qaeda might strike inside the US: “The threat was overseas — that was what George said.” Bush stuck to the same story in his memoir. “Before 9/11, their intelligence pointed to an attack overseas,” he wrote. “On 9/11, it was obvious the intelligence community had missed something big.”

Through a representative, Tenet declined to be interviewed for this article. But the most cursory review of Tenet’s public statements makes clear that Bush either misconstrued Tenet’s position on Al Qaeda to the commission or had simply failed to hear him. In a 1999 Senate testimony, Tenet said “bin Laden’s organization has contacts virtually worldwide, including the United States,” and “all Americans are targeted,” adding, “he will strike wherever in the world he thinks we are vulnerable.” He repeated the warning in early 2001: “Since 1998, bin Laden has declared all US citizens to be legitimate targets of attack.” For Tenet, the Qaeda threat wasn’t exclusively overseas. It was anywhere, at any time.

Bush’s repeated insistence that he was never informed of a specific threat on US soil will be hard to take seriously by anyone who has read the August 6 PDB, which the commission, to its credit, reprinted in full. Bush told the commission that the PDB was “historical in nature.” Indeed, it uses earlier Qaeda attacks for context, but it also contains some prescient warnings: “Al-Qa’ida members—including some who are US citizens—have resided in or travelled to the US for years, and the group apparently maintains a support structure that could aid attacks.” And again, the headline: “Bin Ladin Determined To Strike In US.” But the 9/11 commission chose not to emphasize the degree to which Bush’s own account of what he knew, and what he claimed not to know, was inconsistent with such a stark warning.

Was Bush being deceptive with the commission, or merely defensive?

The answer to that question depends on two unknown facts. One is the content of a second briefing that Tenet gave Bush in Crawford on August 17, 2001. In live testimony, Tenet said at first that he hadn’t spoken with Bush during the entire month of August. Shortly afterwards, he had a representative correct the record and disclose the August 17 briefing. Tenet’s memoir mentions the Crawford trip but doesn’t say what it was about.

Morell, the former deputy CIA director who was Bush’s lead briefer at the time, said Tenet’s August trip to visit Bush in Crawford wasn’t prompted by Qaeda threats. “The reason that George Tenet came down to Crawford,” Morell told Insider, “was that the president said to me one morning, ‘I miss having George in the briefings.'” On the question of whether Al Qaeda came up during the August 17 briefing, Morell said he didn’t remember. If Tenet did give Bush any additional warning about Al Qaeda in Crawford, that would mean that the story Bush gave to the commission was incomplete.

The second loose end is information that Tenet received after the Crawford trip, a memorandum called “Islamic Extremist Learns to Fly.” The memo was about Zacarias Moussaoui, who was later convicted of conspiring to participate in the 9/11 attacks. He most likely would have done so had he not been arrested by the FBI in Minnesota. FBI agents wanted to search Moussaoui’s rooms and luggage; their repeated requests were denied by supervisors. Tenet testified that he didn’t brief Bush about Moussaoui. Bush told the commission he couldn’t recall whether the Moussaoui case had been brought to his attention.

Of course, it’s quite possible that he didn’t. And Moussaoui was just one of the specific leads held by the FBI and the CIA that, had they been pursued, could have exposed the 9/11 plot. Two of the hijackers had already been watchlisted by the CIA, which knew they were in the US. One had made a phone call to a known Qaeda safehouse in Yemen. The commission was right to document the institutional problems underlying these near misses. The CIA and the FBI needed better coordination. They needed clarification from Congress about the limits of their authority, particularly on US soil. But less attention was paid to Bush’s own attitude toward Al Qaeda, and its downstream effect on how cases like Moussaoui’s were handled. If Bush never learned about Moussaoui, is that because Tenet didn’t think to bring it up? Or because he knew that Bush’s focus from the beginning of his presidency was on Saddam Hussein and Iraq and that his appetite for Qaeda-related warnings was quite limited?

What’s clear is that Tenet, for months, had been doing everything he could think of to sound the alarm and get Bush focused on Al Qaeda. So had Richard A. Clarke, who handled domestic counterterrorism in the Bush White House, and reported to Condoleezza Rice, the national security advisor. “We agreed that Tenet would ensure that the President’s daily briefings would continue to be replete with information on Al Qaeda,” Clarke wrote in his memoir. The day after the September 11 attacks, according to Clarke, Bush told him to “see if Saddam is involved” and “look into Iraq.” Clarke famously claimed that he tried and failed to get past Rice so his concerns about Al Qaeda would reach Bush. Clarke wanted counterterrorism to be taken seriously as its own issue at the cabinet level; the record shows it was treated with less urgency, as an extension of US policy in the Middle East and South Asia. Clarke’s inability to make domestic counterterrorism a policy focus for the White House tends to implicate Rice, but it does not absolve Bush. It’s clear that Bush received the same sorts of urgent warnings that Clarke was seeing regularly, from Tenet and the CIA. He just doesn’t seem to have responded, as both Clarke and Tenet did, with a sense of alarm.

A few weeks after the 9/11 attacks, Bush paid a visit to the counterterrorism centre at the CIA. He walked through the corridors, making small talk and shaking hands. “Go get ’em!” someone shouted to Bush, according to a former CIA employee who was there at the time. Bush looked stunned for a moment. Then came his reply: “That’s your job.”

Source: I N S I D E R

Recent Comments