Cornerstone Advisors’ Ron Shevlin says many smaller institutions are still in denial when it comes to AI — and warns that it’s time for them to get off the sidelines.

Ron Shevlin thinks banks and credit unions are having another “PC moment,” except this time the focus is artificial intelligence.

What Shevlin, chief research officer at Cornerstone Advisors, means by that phrase goes back to the beginning of his career. The personal computer had just begun appearing on people’s desks. Young Shevlin was enthusiastically learning to use precursors of Excel and early database programs. He found that senior executives in banking and other businesses resisted the new tools, and swore they’d never touch them. Literally, in some cases, keyboards were considered “secretarial.”

Shevlin couldn’t fathom the resistance.

“This is how we’re going to do stuff!” he thought. Yet “it took five to ten years for PCs to show up on everybody’s desk and just become the way we did business.”

“Roll the clock forward,” Shevlin continues, “and with AI, we’re at the beginning of a new wave of efficiency.” The parallels with the advent of PCs, he says, are uncanny. Early on, much of the software now considered routine didn’t exist and many programs didn’t always work as advertised. But it all came along, though broad usage lagged technological availability.

Now, maintains Shevlin, “we are at the beginning of a new, AI-driven, efficiency curve.”

Many banking leaders are good at fighting daily business fires, but they don’t think conceptually, says Shevlin. As a result, many institutions (apart from the very largest) aren’t yet doing very much with the new tools.

They may be waiting for evidence that AI can drive efficiency. But Shevlin thinks they have to consider the inevitable upward curve.

“The curve is going to be flat for a couple of years yet, because the tools will suck. We won’t know how to use them. And they won’t always work, all the time. But, man, when they do start to work and we start to do stuff, then that productivity curve is going to jump,” Shevlin declares.

After decades of thinking in “programs” and “apps,” insists Shevlin, the dynamic will change.

“The new interface is simply that you type or you talk, ‘Do this. I want to know that. Figure this out for me’.”

No one could deny the productivity gains that began with PCs in the office that culminated in mobile apps that do unimagined tasks today. But Shevlin says many bank and credit union executives remain in one shade or another of denial when it comes to AI.

“They’re coming up with a lot of excuses for not doing anything,” says Shevlin. “But take the average 25-year-old off the street, who has no experience in banking. They don’t know what to ask, but they’re very comfortable with the tools.”

He thinks those extremes need to come together.

What the Numbers Say About Adoption

Shevlin’s comments come from an interview in the wake of the latest edition of his “What’s Going On in Banking” study. (The study is based on just over 300 mostly c-level respondents from banks and credit unions, in the $250 million to $50 billion range, in assets.) His point is not that banks and credit are doing nothing with AI. He thinks the usage could be much higher.

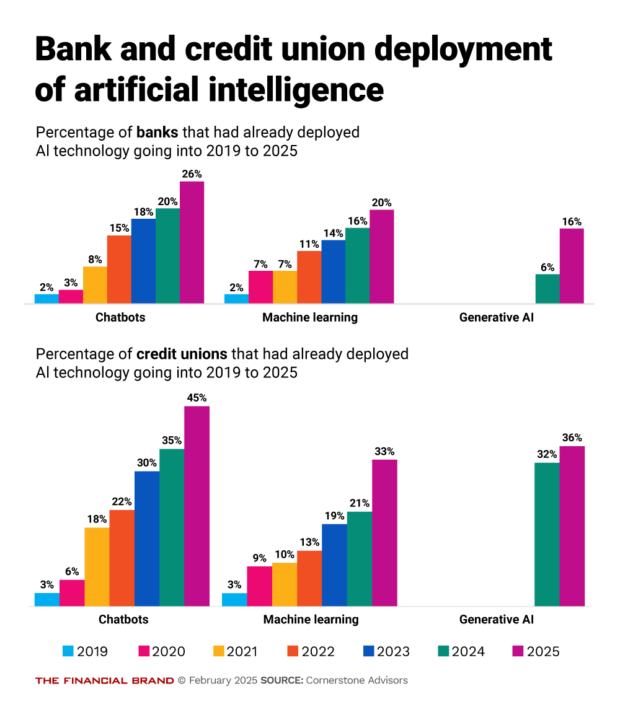

As shown in the pair of charts below, the dominant form of AI used is chatbots — and that is just over a quarter of the responding banks and just under half of the credit unions. Use of machine learning is much less. Use of GenAI is comparatively low among banks, at 16% using it, while it is heavier among credit unions, at 36%. (But Shevlin has an important proviso, which we’ll come to.)

More participation is coming, according to respondents. Among banks, 28% say they will invest or implement GenAI in some fashion in 2025, with 29% of credit unions giving the same response. However, at many institutions, using the various forms of AI is either still at the level of board or executive discussion or “not on our radar,” according to Cornerstone’s figures.

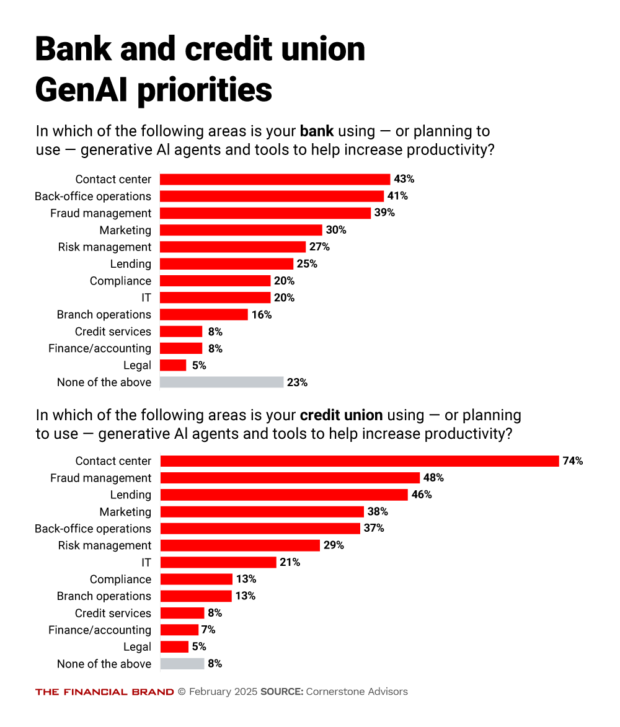

As seen in the next pair of charts, among those institutions using or planning to implement GenAI and related tools, the leading application is in contact centers.

AI Adoption: The Holdups … and the Realities

Shevlin’s sense is that two longtime concerns continue to hold back some institutions.

First, some worry about having issues with their regulators. Shevlin retorts that banking institutions always have regulatory issues, what else is new? The human element of judgment remains critical.

To illustrate this, Shevlin shares a story he uses when he speaks about GenAI, concerning a regional bank that asked a GenAI program to come up with a winning campaign to promote health savings accounts.

The program’s assignment: Raise $2 million in HSAs. And here’s a list of 36,000 prospects.

“So, what did the tool do?” says Shevlin. “First, it created an email account for itself. Then it wrote and tested two different email offers to see which performed better. Over three weeks, every time it learned what would make the offer work better, it made modifications.” The program found that including a deadline stimulated stronger response rates. So did mentioning success stories. Personalization beefed up response rates further.

The three weeks wound up — and the GenAI raised $3 million in HSAs.

But here’s the punchline: “It was all a simulation.”

Why didn’t they really do it? He says the bank worried about turning GenAI loose. Given a mission, it might have, say, made rash promises, like, “You’re going to get rich by putting money into an HSA,” says Shevlin — the kind of offer that’s a red flag to consumer examiners.

Even at this AI-friendly bank, the trust is not there yet. “They wanted to see what the tools could do, but they knew that in a real application human involvement is necessary,” says Shevlin.

A second concern, related to the first, is that bank and credit union executives fear that bias problems are hidden in their data, potentially tainting AI credit analysis to GenAI interactions.

Counters Shevlin: The bias problem in data is there whether or not the institution applies AI tools to it. It’s always lurked in the background, not only within institutions’ own files, but also in external factors such as credit scores. (In fact, one concept of evaluating fair lending performance, the “disparate impact” standard, holds that bias can occur unintentionally if lending standards inadvertently set up policies that hit protected applicant groups disproportionately.)

Ultimately, he believes, both institutions and their regulators have to modulate their judgment in regard to AI.

“My argument has long been, don’t regulate technology — regulate behaviors and output,” says Shevlin. He thinks some regulators have actually begun to accept the argument that it’s underlying data, and assumptions made in the gathering of it, that can generate bias, rather than the technology producing lending decisions.

Just when leaders at smaller institutions and regulators will have a meeting of the minds remains to be seen. But Shevlin adds that leaders must rise above compliance concerns to think about efficiencies. (He also thinks institutions should resist any regulatory attempt to dictate technology.)

Assuming that the bank or credit union is making a sufficient number of loans to justify the investment in AI tools for lending, management needs to consider the value of better credit analysis.

This, he says, includes “getting loans out the door faster, handling them more efficiently, with the added benefit of potentially making better lending decisions on both sides — lending more to people who qualify and lending less to people who shouldn’t be getting credit.”

Ultimately, “it’s a bank-by-bank decision.”

What Leaders Need to Realize Is Really Going On

Shevlin adds a big P.S. to everything he’s said about how bank leaders are thinking about GenAI. Just saying no in the bank stops at the front door. This is another reason that Shevlin believes the institutions his study covers are having the “PC moment.”

Back in the 1980s, PCs began to infiltrate banking offices. These were the days of heavy desktop machines with full-size cathode-ray tube monitors. They didn’t leave the building.

Shevlin says the IT departments began issuing edicts about not putting unapproved applications on company PCs, asserting control.

And staffers routinely ignored the edicts. Where they couldn’t get away from that, as more and more began to own their own PCs, they simply installed what they wanted to use on their home machines.

Analogously, in some areas, executives are living a fiction when it comes to GenAI today.

“The bankers who are saying, we’re not going to do anything, we’re going to be fast followers, well, they don’t understand — or are willfully ignoring the reality — that everybody in their organization under the age of 30 is already using these tools,” says Shevlin.

Many may be using agentic GenAI tools for personal tasks, like making dinner reservations.

It isn’t ending there. For example: “Marketing is already creating content with ChatGPT,” says Shevlin. “They’re creating taglines, advertisements and visuals using ChatGPT. They’re better than what’s coming out of your marketing agency.”

But Shevlin says there’s another lesson from the PC Moment financial institutions must take now.

Many programs were amended on the fly, for example, formulas in spreadsheet program cells. Shevlin says some of those changes were hard-coded by people who left the bank, and no one ever documented the changes or the reasoning. And some of that stuff, he says, was wrong.

The same lack of documentation goes on now, Shevlin warns. Where a human has tasked AI, not recording how the tasking was done — it can be an iterative process — makes it a buried mystery. Transparency, training and documentation are musts.

Says Shevlin: “A 50-year-old chief marketing office asking ChatGPT to do something is going to ask something very different from the request made by a 25-year-old with only a year or two of experience.”

Source: THE FINANCIAL BRAND

Recent Comments